Exploring Italian decadence through magic. We can do it thanks to two movies released half a century away.

In 1963 Federico Fellini directed “8½”. The film is a journey into the mind of a director with a writer’s block. In one scene, the protagonist Guido Anselmi, starring Marcello Mastroianni, runs into an illusionist particularly revved up – Maurice (Ian Dallas). Along with his assistant Maya (Mary Indovino), the shouting magician performs a mind reading effect. When Maurice approaches Guido, the psychic reads in his mind some mysterious words: “ASA NISI MASA.” The scene is followed by a long flashback revealing the origin of the strange words. When he was a child, the director used the phrase as a magic formula; pronounced in the right way, he was able to move the eyes of a man portrait in a painting, making them point in the direction of a hidden treasure.

According to the critic Paul Meehan, the scene would refer to the enigmatic side of the creative process, so as to be impenetrable even to a mind reader. (1)

Fellini’s look on the magician is benevolent, and the scene full of charm. We can hear the echo of the meetings with Gustavo Rol, the alleged psychic from Turin, who not only pretended to read minds, but he could also remotely “change” paintings, using special magic formulas. Again in Turin, the eyes of the Statue of Faith, in front of the Gran Madre di Dio Church, would look in the direction of a mythical treasure – the Holy Grail, buried somewhere in the city. The scene of “Maurice the magician” seems permeated by the themes of the conversations held by Fellini in the charming rooms of Gustavo Rol’s house.

Even “La grande bellezza” by Paolo Sorrentino tells the story of an artist in crisis. Today’s guest of “La Repubblica delle Idee” event, the director has already dedicated to “Silvan the magician” affectionately bitter words in his book Tony Pagoda e i suoi amici (“Tony Pagoda and his friends”). (2)

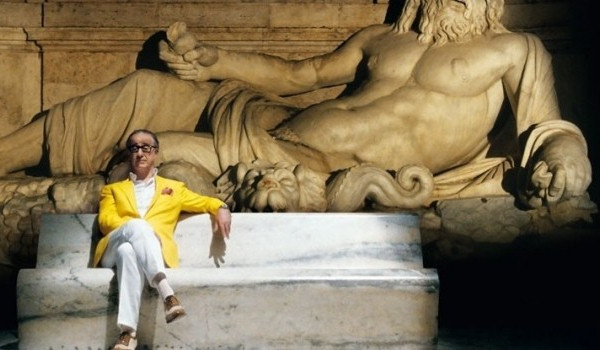

As in “8½”, the protagonist of “La grande bellezza” – Jep Gambardella (Toni Servillo) – comes across an illusionist.

The total beauty of the Terme di Caracalla with daylight […] and, against the background of monumental baths, in the meadow, alone with his unreal five feet high, illuminated by the headlights, there is a giraffe. […] Not far from the giraffe, electricians and various laborers, indifferent even to the giraffe, smoke and talk about football as if nothing happened. Jep, his mouth open in astonishment, fixes the giraffe. He approaches a man of about fifty, tall, elegant, surgically “adjusted”, with a slim cigarette in his hands. His name is Arturo. (3)

Another reference to the city of Turin? Arturo Brachetti does not smoke, but is the most fascinating among Italian contemporaries illusionists.

Jep: Arturo, what are you doing here?

Arturo: What am I doing? I am preparing my magic show. This is the main effect of tomorrow night. The disappearance of the giraffe.

Jep: Will you make the giraffe disappear?

Arturo: Of course I do disappear the giraffe.

Jep: So, Arturo, why do not you make me disappear too? (4)

Fifty years after Fellini, however, Sorrentino’s magician is powerless. And he does not hide it.

Arturo: Jep, think about it: if you really could make someone disappear, would I still be here, at my age, to do these silly things? It’s just a trick. (5)

A half-century later, the real magic of Maurice has given way to the bitter awareness that it is just a trick. Only a trick. But in spite of its bitterness, Sorrentino gets aspects of enchantment, entrusting Jep a final monologue in which life is captured in its most intense and conflicting fragments:

The silence and the feeling. The excitement and fear. The sparse, erratic flashes of beauty. And then the squalor and the wretched miserable man. All buried by the blanket of the embarrassment of being in the world. (6)

All valuable despite the disenchantment. Despite the awareness that

In the end, it’s just a trick. Yes, it’s just a trick. (7)

1. Paul Meehan, Cinema of the Psychic Realm: A Critical Survey, 2010, p. 49.

2. “Eventually, when everyone will die, Silvan will survive. It is immortal, like the rock. If you stare closely into his eyes, in his stuck hair, in his lean physique, you say: he is thirty years old. Look at him a moment later and say he is one hundred and thirty.” in Paolo Sorrentino, Tony Pagoda e i suoi amici, Feltrinelli, Milano 2012, chapter 3.

3. Paolo Sorrentino e Umberto Contarello, La grande bellezza, Skira 2013.

4. Ibidem.

5. Ibidem.

6. Ibidem.

7. Ibidem.

BY-NC-SA 4.0 • Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International