Mariano Tomatis

In Search for Gothic Magic

"A Night at the Villa Diodati and the Birth of Frankenstein", British Library, 30 October 2018.

See here the slides with text.

At the core of the Gothic lies the representation of a conflict: the one between an enchanted Past, a lost world peopled by inexplicable and disquieting phenomena, and the Present dominated by Enlightenment, trying to destroy that world.

Started in 1764 as a literary genre with The Castle of Otranto by Horace Walpole, its themes have soon been translated into other media. In 5 years it conquered the theatrical stages with The Mysterious Mother (1769), a Gothic drama by Walpole himself. The 20th century saw the birth of Gothic movies in the 30s and Gothic rock at the end of the 60s. Today we are used to expressions like Gothic comic books, video games and TV series, but with this talk I will try to identify a theatrical context in which Gothic topics had been translated in a very peculiar way: the underground and rather unexplored world of stage magic.

Forget about the fluffy-bunny magic for kids: I will focus on a specific performing art designed for adults, dating back to the middle of the 18th century. In that period, some stage magicians fueled the conflict between Rationality and Irrationality by developing and staging knowingly ambiguous theatrical narratives, mixing the two ingredients of horror and mystery.

Imagine a rose floating in mid-air between the hands of a magician. Levitation is what we perceive, and we call it “effect”. We know that objects do not levitate, so what we see is impossible and the effect is magical. But even if it seems real, it is just illusory: to keep the flower in mid-air, the magician is using a wire, so tiny that it is almost invisible; the use of a wire is the “real method” employed. The illusory effect triggers a sense of wonder and is enjoyable as long as the real method is kept hidden.

Now travel back with your mind to Paris in 1783. The man on the stage presents himself as a Professor and Demonstrator of Physics. He sits near an automatic figure about eighteen inches in height: The Grand Sultan. The automaton nods in answer to questions propounded, and seems to be able to read minds, striking a bell with a hammer a number of times equal to the value of a playing card thought of. Even if it is just a mechanical contraption, made up of cogs and pistons, it gives the impression of being gifted with intelligence and having a conscience.

Left: Henri Decremps, La magie blanche dévoilée, Chez l'Auteur, Paris 1784 (frontispiece). Right: The Grand Sultan (detail).

The man who is operating it comes from Tuscany, Italy. His name is Giuseppe Pinetti. Disguised under the clothes of a scientist, Pinetti is a stage magician, a con-man denying his own nature. The way he presents himself is in line with his epoch, since Enlightenment has declared the supremacy of science over magic. The scientific narrative frame around his tricks subtly manipulates the perception of the audience. The construction of that frame is based on the revelation of a “false method” which seems scientifically sound and explains the surprising effect. The “real method” involves an accomplice, moving the automaton like a puppet with the help of a set of wires. Concealing the existence of the man behind the curtains, Pinetti explains that the intelligent, self-moving robot is the result of the most advanced technology applied to mechanics. Even if it is a lie, the idea is in the realm of possibility: the existence of a very simple brain like the Pascaline – the mechanical calculator created by Blaise Pascal in the early 17th century – makes it credible in some way.

A Pascaline, the mechanical calculator created by Blaise Pascal.

The enlightened spectator can laugh in the morning at the street magician performing the cups&balls trick and enjoy to be knowingly fooled by sleight of hand. The same spectator can applaud, in the evening, a scientific demonstration by Professor Pinetti and celebrate the extraordinary achievements of technology before the miraculous automaton. Unaware of the common nature of the two experiences.

The evening deception is a bit different from the morning one. Cups&balls are funny, the Grand Sultan is eerie. The sense of eerieness experienced by the spectators is due to the obscure agency making it move and act like a human being. Using the expression by Mark Fisher,

there is something where there should be nothing. (1)

Pinetti offers an experience which is the theatrical translation of a typical Gothic ingredient: mysterious movements, apparently revealing an intention. Consider for example the sable plumes on the giant helmet in The Castle of Otranto. Sometimes, as if triggered by specific events in the novel, they start to swing.

[Before] Manfred could reply, the trampling of horses was heard, and a brazen trumpet […] was suddenly sounded. At the same instant the sable plumes on the enchanted helmet […] were tempestuously agitated, and nodded thrice, as if bowed. (2)

They nodded thrice. Maybe a three of clubs was chosen?

The giant helmet from The Castle of Otranto

Unlike the readers of the novel, spectators share the same physical space with the self-moving contraption, just a few meters from them, and what happens – here and now – just before their eyes does not require any willing suspension of disbelief. It is a typical Gothic experience, the one lived during Pinetti’s show: with his Grand Sultan, the magician successfully reenchants an otherwise disenchanted audience.

Pinetti is so successful that many plagiarists start to present the same tricks in other countries. In 1789 Mr. Philidor, Professor and Demonstrator of Physics, presents his Grand Sultan in Berlin. Less talented than his Italian colleague, he doesn’t find favour with the audience. Failure drives him to find his own way and radically alter the mood of the show, involving his spectators in a scarier experience which owes a lot to the Gothic imagery: the evocation of Ghosts or phantasmorasi.

Illustration of a performance by Philidor, from a 1791 handbill.

With Philidor, the influence between stage magic and literature is reversed: novelists start to use the rational explanation of magic tricks as an ingredient to balance the enchantment produced by real magical happenings. In his Ghostseer (1789), Friedrich Schiller stages a ghost evocation by a Sicilian necromancer and his mate, two characters portrayed on the models of the Count of Cagliostro and his master Althotas. The main character is involved in a series of seemingly paranormal feats, but then the Sicilian is captured by the police. When in jail, he explains in detail the trickery employed to make the ghost appear in a coffee house near Venice. Philidor the magician and Schiller the novelist are both inspired by the same necromancer: a man called Schröpfer running a coffee house in Lipsia.

Imagine to be an historian, interested in retracing the exact procedure followed by Philidor to make a ghost appear. Historical truth pops out from the interaction of three elements: newspaper clips, books about magic tricks and Gothic novels. Newspapers often record the exact words pronounced during the show and describe the apparitions from the spectator’s point of view. According to La Feuille Villageoise, Philidor opens his show with a supremely ambiguous disclaimer:

I am not a priest nor a magician; I don’t want to cheat you, but I am sure I will amaze you. (3)

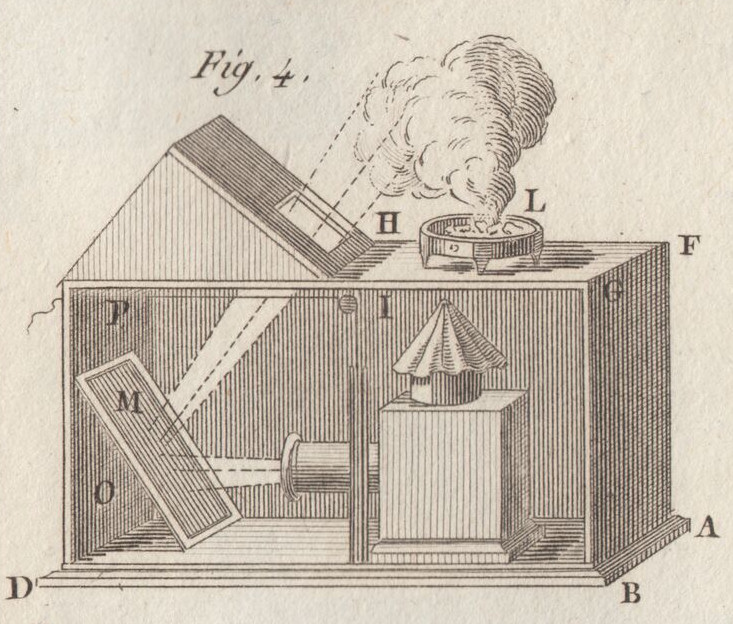

Recreation 64 from Guyot’s encyclopedia of magic tricks is titled “Make a ghost appear on a pedestal in the center of a table” (4) : it describes a magic lantern hidden in a wooden box, projecting the image of a ghost on the smoke coming out of a burning brazier.

Edmé-Gilles Guyot, Nouvelles récréations physiques et mathématiques, Paris 1792.

The result is a striking ectoplasmic shape, hovering above an upright plinth forming a kind of hallucinatory altar, whose voice is lent by an accomplice. If you try this at home, you immediately discover that the method has a huge limitation: after a few seconds, the air is unbreathable because the room is full of smoke. How could Philidor use it on an indoor stage? Unlike the practical manual by Guyot, which doesn’t solve the problem, the Gothic novel by Schiller meticulously explains how to deal with it. In the Ghostseer the image on the smoke lasts just a couple of minutes, then the door is opened, the room is ventilated and a figure in flesh and bones enters, directly interacting with the audience. The man is an accomplice dressed like the figure projected on the smoke, being a sort of materialisation of the ectoplasmic shape.

In 1798 another stage magician performs in Paris disguised as a scientist: Étienne-Gaspard Robertson brings the phantasmorasi – renamed phantasmagoria - to a level never achieved before. Thinking like a novelist, Robertson conceives a narrative thread linking Luigi Galvani’s experiments with bioelectricity and the ghost show. Robertson welcomes his spectators into a room accessorized like a physics laboratory, presenting the experiment of the dead frog whose muscles twitch when struck by an electrical spark. By defining the Galvanic fluid “a resuscitating agent”, he implies that also dead people can be brought back to life. Ghosts are evoked only when the scientific framing is completed. In full darkness, scary images are thrust in the face of the audience, giving life to a dramatic clash between reason and benighted beliefs.

Etienne Gaspard Robertson, Mémoires Récréatifs, Scientifiques et Anecdotiques du Physicien-Aéronaute E.G. Robertson, Vol. 1, Chez l’Auteur, Paris 1831 (frontispice).

Until then, resurrection has always been a matter of faith; with Robertson, the impossible gains a kind of scientific plausibility. According to Gian Piero Brunetta, in the revolutionary Paris

there are too many unburied bodies, too many heads separated from their trunk, too many violated graves, not to imagine that some of these wandering souls can not be captured by the magic of Robertson. (5)

Mirroring Philidor’s ambiguity, a reviewer of the show states that “there is no trick, no deception nor illusion” because the Galvanic fluid can “astonish and marvel even most educated and less credulous people” (6) . Mary Shelley’s Doctor Frankenstein will employ another electrical spark to bring a body back to life, playing on the same ground of plausibility.

The influence of Gothic novels on Robertson’s show becomes explicit when the magician announces the apparition of the “Bleeding Nun” from Matthew Gregory Lewis’ dreadful novel The Monk (1796). The expression is enough to make the spectators shudder, because most of them know that it is a controversial book, mixing ingredients like eroticism, violence, perversion, and the supernatural. The provocative advert is a perfect marketing strategy and the apparition of the nun, approaching the audience with a dagger in her hand, comes one century earlier than the Train Pulling into a Station, the film directed by Lumière brothers showing the moving image of a life-sized train coming directly at the spectators.

Robertson 1831, 342-3.

Technically speaking, the illusion is created with a couple of magic lanterns. One is fixed in front of the screen, hidden in a small cabinet; it projects the image of the cloister. Another one is the fantascope behind the screen, mounted on wheels; moving backwards, the nun increases in size and seems to get closer to the audience. (7)

Robertson’s magic consists in making visible what is invisible: the human soul. Reversing the process, in 1800 the doctor Laurent announces the discovery of a technical process to make invisible what is visible: the human body. Visitors are welcomed in a room with a transparent trunk suspended in mid-air. Nothing can be seen inside, but asking for something, spectators get an answer from an invisible lady. The voice comes out of an acoustic horn, whose mouthpiece is placed near the lips of the girl.

It is just a theatrical illusion: the girl is hidden in the superior room, she can look at the spectators through a hole in the ceiling and speak to them with the help of the horn, whose tube secretly reaches her secret seat. By the end of the year in Paris, three invisible ladies meet paying spectators in different places and two theatres produce vaudeville plays about the show, both based on the amorous misunderstandings related to the possibility that a girl becomes invisible.

The debate on the scientific plausibility of the feat throws an oblique light on the concerns of the time about women’s position in the public eye. Jann Matlock investigated the topic (8) from the very direct question “why a woman and not a generic person?”. A fruitful starting point, applicable to almost all contemporary grand illusions, all based on the idea of torturing women – sawing them in half, for example – and restoring them. According to a commentator of the time [Louis-Sébastien Mercier],

twenty years ago, girls would not have set foot out of their fathers’ houses without their mothers, walking under their wings with eyes religiously lowered. […] The Revolution changed that subordination; they run around morning and night with complete liberty. (9)

Invisibility is a virtue to be celebrated and a countermeasure to the challenges posed by women’s emancipation.

The scariest story related to the invisible woman is the one about a magician called Charles Rouy. Eyewitness of Louis 16th’s beheading in 1793, his gory report is one of the most quoted in the books about the French Revolution. After a successful season of his “invisible woman” in Paris, in 1802 he leaves his wife and moves to London with another woman. The wonders of invisibility now tantalize crowds in a room in Leicester Square. We don’t know the identities of the women locked in those narrow spaces, making the miracle possible. Most probably, the work is enlisted to the wives: Marie-Joséph Stevens in Paris, Henriette Chevalier in London. Charles Rouy has two children: Claude Daniel from the first wife and Hersilie from the second. Mirroring in a perverse way the activity of his father, some years later Claude Daniel declares his sister illegitimate and makes sure that she is incarcerated in six different asylums for fourteen years. Hersilie denies to be insane and fights for her sanity to be recognized, rejecting the imposed invisibility. In order to find her way out, she spends much of her time writing while incarcerated, using for ink whatever is available, even her own blood. Her writings weave a web of supporters and document the abuses of the psychiatric system. Against all odds, the strategy works: in 1868 she is released, declared cured and compensated for her troubles. Published in 1883, her memoirs will become a literary success and are now considered a classic of psychiatric literature. The life of Hersilie Rouy would offer a perfect plot for a Gothic novel: brought up by a couple of stage magicians, in the shadow of an invisible mother, in the context of a relationship marked by sadistic elements, declared illegitimate by her step brother, deprived of her name and imprisoned, the woman is the perfect character for a horror story with a heartening twist of female redemption through the power of words.

In order to end on a lighter tone, tomorrow night will be Halloween and you may be in search for ideas to make that day memorable. I will share with you three practical ways to amaze your friends, making them experience truly Gothic experiences.

A ghost on your windshield

Some months ago, wrapped in its blanket, a ghost appeared on my windshield and I could capture its image with my camera.

Turin (Italy), 10 March 2018.

No CGI in this shot. The basic idea behind this illusion is French: in 1852 Pierre Séguin patents an optical toy called Polyoscope. By looking inside a box, a ghost figure appears to be standing within the apparatus. Ten years later, in London, Henry Dircks and John Henry Pepper bring the idea to the public attention making it big enough to fit a theatrical stage. In order to understand the principle at work, imagine yourself in front of a window at night: as you approach it holding a candle, you can easily see your own illuminated image, superimposed in the dark images outside. The sheet of glass can be transparent and a mirror at the same time: this is the secret of what we today call “the Pepper’s Ghost Illusion”, an archetype of Victorian stagecraft. At the time it was also labeled “living phantasmagoria”, because actors in flesh and bones could act like ghosts and interact with actors just exploiting the reflection on a giant sheet of glass installed at 45 degrees on the stage.

In order to install a Pepper’s Ghost in your car, print the image of a ghost (download) and cut it out with a pair of scissors. Then insert the paper ghost inside the car between the glass and the dashboard, where you usually put the parking ticket. Looking at it from inside the passenger compartment, the ghost is reflected in the glass and shows the classic semi-transparent appearance of the disembodied spirits.

The Death’s Head 2.0

In “The Death’s Head” from Fantasmagoriana, Friedrich Schulz tells the story of Calzolaro, a stage magician setting up

a species of phantasmagoria dessert after supper; an unexpected spectacle. […] If all succeeds, no one will be exempt from a certain degree of terror. (10)

The idea is to make a death’s head speak with the help of a ventriloquist.

If you don’t have a real skull nor a ventriloquist, you can buy for a few quid a plastic cranium and a Bluetooth speaker. Heat a blade to make a hole below the skull and hide the speaker inside. By connecting your mobile phone via Bluetooth, you can make your Death’s Head speak with a pre-recorded MP3 or with the voice of an accomplice calling you from the next room.

Nightmare in Hyde Park

In his short tale “The Horla”, Guy de Maupassant tells this shocking story:

I got up so quickly, with my hands extended, that I almost fell. Horror! It was as bright as at midday, but I did not see myself in the glass! It was empty, clear, profound, full of light! But my figure was not reflected in it. (11)

The same happened to me, here in London. I found myself near Hyde Park Corner. I went to the public toilets and approached the sinks. Casually raising my gaze, I search for myself in the mirror—but fell into the nightmare described by Maupassant: everything was reflected except my image, and I was involved in a totally unexpected magical experience.

London (UK), 17 October 2014.

Again, no CGI in this shot. The mirrors had been actually removed, probably due to damage: only the frames remained, dividing two rows of perfectly symmetrical sinks that created the illusion of a reflection. The magic can still be experienced, in the public toilets near Hyde Park Tube Station – unfortunately, just in the gentlemen’s toilet. Looking rationally at the larger room, everything becomes clear: the arrangement of the fixtures and the lack of the mirror suggest—by pure chance—the presence of a reflective surface. This confirms in me the belief that a magical experience can emerge from anywhere, without any human intervention.

The secret is to be attuned to perceive it, because—as François Truffaut used to say—

life has way more imagination than we do.

Many thanks to Laura J. Mann for her help.

Note

1. Mark Fisher, The Weird and the Eerie, Duncan Baird, London 2016.

2. Horace Walpole, The Castle of Otranto. A Gothic Story, John Murray, London 1769, 87.

3. "La Phantasmagorie", La Feuille villageoise, N. 22, Paris 28.2.1793, 490.

4. Edmé-Gilles Guyot, Nouvelles récréations physiques et mathématiques, Recreation 64, Vol. 3, Gueffier, Paris 1770, 186-90.

5. Gian Piero Brunetta, Il viaggio dell’icononauta, Marsilio, Venice 1997, 318-9.

6. G.D.L.R., Courrier des spectacles, 6 germinal Year VIII, 4.

7. Etienne Gaspard Robertson, Mémoires Récréatifs, Scientifiques et Anecdotiques du Physicien-Aéronaute E.G. Robertson, Vol. 1, Chez l’Auteur, Paris 1831, 342-3.

8. Jann Matlock, "The Invisible Woman and Her Secrets Unveiled", The Yale Journal of Criticis, Fall 1996, 175-221.

9. Louis-Sébastien Mercier, Journal des dames, 15 brumaire Year VIII, 66-8 quoted in Matlock 1996, 183.

10. Friedrich Schulz, "La tête de mort" in Fantasmagoriana, F. Schoell, Paris 1812, 244.

11. Guy de Maupassant, Le Horla, Paul Ollendorff, Paris 1896, 61-62.