Chess, Knight's Tour and Secret Codes

Detailed analysis of the Great Parchment of Rennes-le-Château

Article by Mariano Tomatis

The Priory of Sion is a fraternal organization, founded and dissolved in France in 1956 by Pierre Plantard. In the 1960s, Plantard created a fictitious history for that organization, describing it as a secret society founded in the Kingdom of Jerusalem in 1099, which serves the interests of the Merovingian dynasty and its alleged bloodlines. This myth was expanded upon and popularized by the 1982 controversial book The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail, and later claimed as factual in the preface of the 2003 conspiracy fiction novel The Da Vinci Code.

To give credibility to the fabricated lineage and pedigree, Plantard and his friend, Philippe de Chérisey, needed to create "independent evidence". So during the 1960s, they created and deposited a series of false documents, the so-called Dossiers Secrets d'Henri Lobineau ("Secret Files of Henri Lobineau"), at the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris. During the same decade, Plantard commissioned de Chérisey to forge two medieval parchments, which contained encrypted messages that referred to the Priory of Sion. They adapted, and used to their advantage, the earlier false claims put forward by Noël Corbu that a Catholic priest named Bérenger Saunière had supposedly discovered ancient parchments inside a pillar while renovating his church in Rennes-le-Château in 1891. Inspired by the popularity of media reports and books in France about the discovery of the Dead Sea scrolls in the West Bank, they hoped this same theme would attract attention to their parchments. Their version of the parchments was intended to prove Plantard's claims about the Priory of Sion being a medieval society that was the source of the "underground stream" of esotericism in Europe.

One of the two parchments, with the longer text, is known as Great Parchment: it was published for the first time in 1967 by Gérard de Sède on page 109 of L'Or de Rennes. In this page, a detailed report of its creation is given, with references to its sources, based on the analysis of its structure and the messages hidden within it.

The complete process of creation in detail.

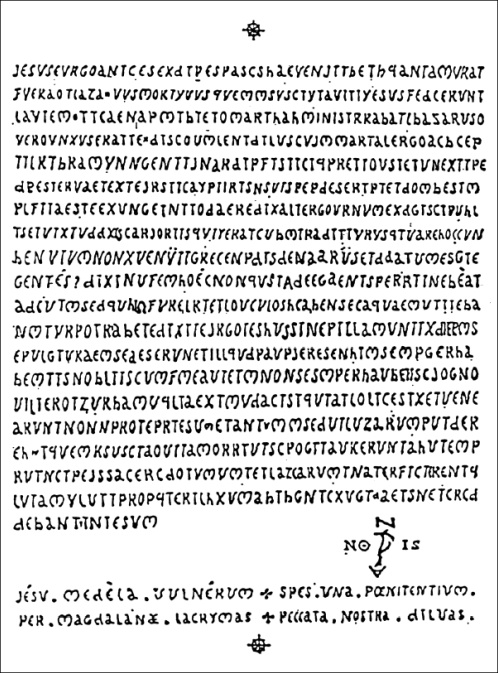

The Great Parchment [download] is the result of the fusion of two elements: a long Latin text taken from the Gospel of St.John (12:1-11) in the Vulgate translation and at least 3 shorter messages: 128, 12 and 8 letters long.

Two of the three messages (one encrypted, the other not) have been inserted - at almost regular intervals - inside the Gospel text. A third 8-letter message (REX MUNDI) has been written with a smaller font. The parchment has been written with a pseudo-uncial font, which shows some elements which are not coherent with the style of the font used from 3rd to 8th century (for example, the use of a question mark at line 10). The pseudo-uncial font has been studied by Ferdinando Ferraioli(1).

The three hidden messages

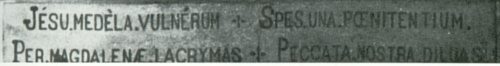

One of the three messages is AD GENESARETH. In the context of the parchment, which closes with two lines which refer to Mary Magdalene (coming from the old - and now stolen - bas relief at the foot of the altar inside the church at Rennes-le-Château) the two words ("at Genesareth") clearly refer to Mary of Magdala; the town of Magdala is on the lake of Genesareth.

A second message is REX MUNDI: in Cathar tradition, Rex Mundi (King of the World) was the king of Evil, opposed to the king of Good, identified with God.

The third and more complex message - mentioned for the first time in a small book signed by "Madeleine Blancasall" (but probably written by Pierre Plantard) and recorded in the French National Library in Paris on August 28, 1965 - has been created by using 128 letters taken from two documentary sources:

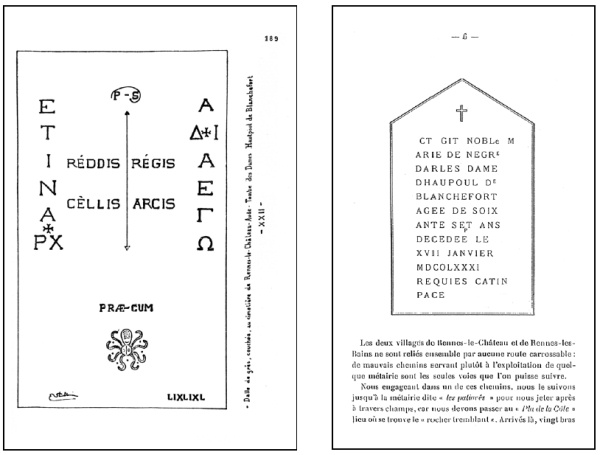

1) Table 22 from Pierres Gravées du Languedoc (a book attributed to Eugène Stüblein, but probably written by Pierre Plantard) mentioned for the first time in the same Blancasall booklet(2): we shall refer to it here by the name "REDDIS stone";

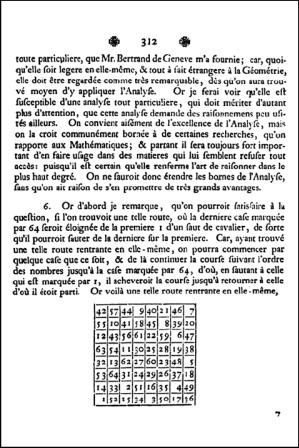

2) An image from Elie Tisseyre, "Une excursion à Rennes-le-Château", Bulletin de la Société d'Etudes Scientifique de l'Aude, Vol.17, 1906 (Download)(3): we shall refer to this by the name "CT GIT stone";

On the left: Table 22 from Pierres Gravées du Languedoc (a book attributed to Eugène Stüblein). The table appeared for the first time at the end of the booklet signed "Madeleine Blancasall".

On the right: Elie Tisseyre, "Une excursion à Rennes-le-Château", Bulletin de la Société d'Etudes Scientifique de l'Aude, Vol.17, 1906.

9 letters have been taken from REDDIS stone, while from the CT GIT stone all the available letters have been used (119 letters), for a total of 128 letters. The sum has not been chosen at random: the author wanted to scramble the message by using a chessboard, so any multiple of 64 letters would have been good. Probably when the author chose the CT GIT stone and he found only 119 letters, he had to find 9 additional letters - and he used the REDDIS stone - in order to get 128 letters. Moreover, we have no documentary proof of the existence of REDDIS stone except for recent pictures in some way linked to "treasure hunters", and no one has ever seen it (the oldest text with the PS PRAECUM letters is the report attributed to Ernest Cros, which deals with the 1959 events). Probably the author of this parchment is the same one who created the first picture of the stone - possibly on the basis of older material - needing it to get 128 letters and giving its reproduction for the first on the booklet by Madeleine Blancasall. The CT GIT stone has a more solid history, having been reported by a team of archaeologists from the Société d'études scientifique de l'Aude (SESA).

The letters from the two stones are:

CTGITNOBLEMARIEDENEGREDARLESDAMEDHAUPOULDEBLANCHEFORTAGEEDESOIX

ANTESEPTANSDECEDEELEXVIIJANVIERMDCOLXXXIREQUIESCATINPACEPSPRAECUM

The author scrambled the letters by starting with this anagram:

BERGERE PAS DE TENTATION QUE POUSSIN TENIERS GARDENT LA CLEF PAX DCLXXXI PAR LA CROIX ET CE CHEVAL DE DIEU J'ACHEVE CE DAEMON DE GARDIEN A MIDI POMMES BLEUES

We shall refer to it as the "BERGERE message".

The author could have chosen any other anagram, and it is interesting to analyse the reasons why he chose "those" words and not others. In this article we shall not deal with this issue.

At first sight it is obvious that he chose ideas in some way related to Rennes-le-Château and to an esoteric scenario. However, the "structure" of the result shows clearly its nature as an "anagram of a previous message". The CT GIT stone epitaph was written in 1781, and it is a typical mortuary text; the BERGERE message shows all the typical properties of an anagram. Italian expert Stefano Bartezzaghi (the "alchemist of alphabets") would define the complete sentence as "raccogliticcia" (cobbled together)(4), because it is far from idiomatic, being a mixture of terms linked together without a clear sense and without the typical "musicality" of a well defined sentence.

Mike Morton suggests "Bad credit" as a good anagram of "Debit card". It is a very good anagram, because both "Bad credit" and "Debit card" are idiomatic sentences. But with the same letters you can get "Crab Tided", which is far from a good anagram (it is "raccogliticcio"!).

The BERGERE message shows all the limitations connected with its nature in particular in the two words PAX DCLXXXI, which clearly seem to be used in order to "recycle" the great number of Roman numerals in the CT GIT stone.

Paul Saussez was very good in suggesting an alternative anagram in this post, mixing ideas related to Rennes-le-Château mythology:

VOICI LE SECRET DE L'EPITAPHE: JESUS ET MARIE DE MAGDALA DORMAIENT EN PAIX AU TOMBEAU DE RENNES QUE SAUNIERE VIOLA, SION LE FIT CHANGER DE PLACE. PS DDDCCCXXXX

Here is the secret of the epitaph: Jesus and Mary of Magdala rest in peace at the tomb in Rennes which Saunière violated, Sion swapped them. P.S. 1840

Obviously "P.S." stands for Paul Saussez! Saussez work gives enough evidence of the fact that the BERGERE message is one of many which could have been chosen by using only the 128 letters on the two stones.

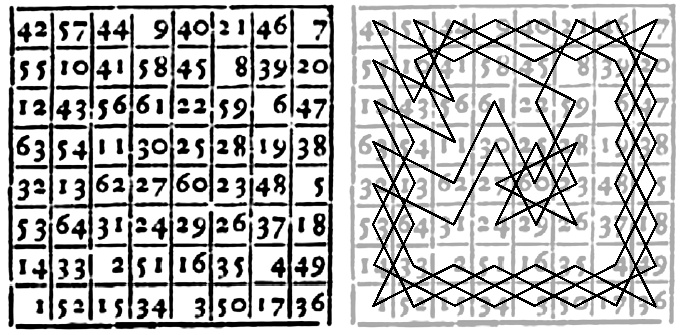

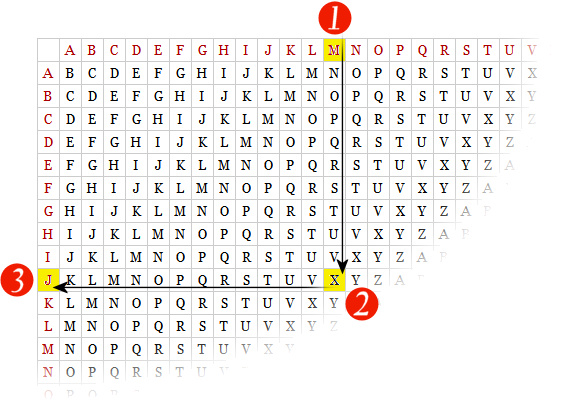

Once the message was chosen, the author decided to write it on two chessboards by following the Knight's tour. The number of possible Knight's tours is enormous, but its author chose one of them: the first "cyclic" one given by Euler in 1759 in his Memoires de l'Academie Royale des Sciences et Belles Lettres (Download)(5). I am proud to be able to announce having found it, because so far no-one has ever given any reference to Euler's tour published on 1766 (and, more important, there is no need of any source for discovering it: the structure of the message speaks for itself!).

Euler, "Solution d'une question curieuse qui ne paroit soumise à aucune analyse" in Memoires de l'Academie Royale des Sciences et Belles Lettres (1759) 15, Berlin: 1766, page 312.

A cyclic tour is the one which allows you to link the ending (64) and the starting (1) squares, in a way "closing" the path and making it cyclic.

The first cyclic tour suggested by Euler

By choosing a cyclic path, the author granted himself the possibility of choosing the square from which to start writing the message. The idea of changing the starting square was mentioned by Euler himself in the cited article. On page 313 we read:

After having memorized a cyclic path, you will be able to solve the problem by starting the tour from any square. For example you can start from the square 25 by placing the knight on it, then move to squares 26, 27, 28... until square 64. Now move to square 1, from which you can move towards square 2, 3, 4... until you reach square 24; you will have covered all the squares on the chessboard.

The complete article written by Euler is a collection of techniques which can be used to define a new path from any other given one(6). For example, on page 311 he suggests to invert the path:

Inverting the same path, it will be possible to start from square 64, move to squares 63, 62, 61, etc. reaching, after having covered all squares, to the square 1.

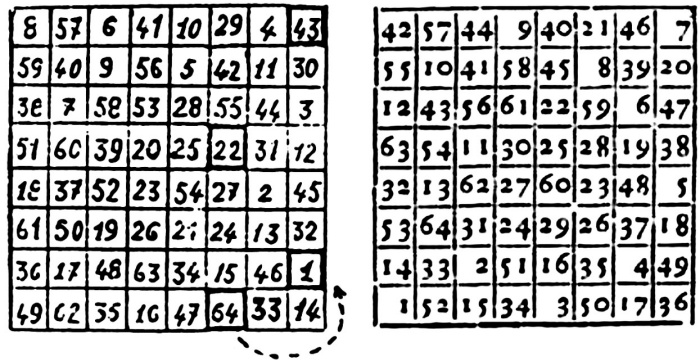

Pierre Plantard was aware of the possibility, suggested by Euler, of changing the starting square. According to Jean-Luc Chaumeil(7), Pierre Plantard presented a shifted version of the correct (and cyclic) Knight's Tour in his Rennes-le-Château conference at Corbu's Hotel de la Tour on juin 6th, 1964.

The same Tour can be found in Norberto, "Le symbolisme de l'echiquer" in Vaincre 3 (septembre 1989), pages 17-19 (download).

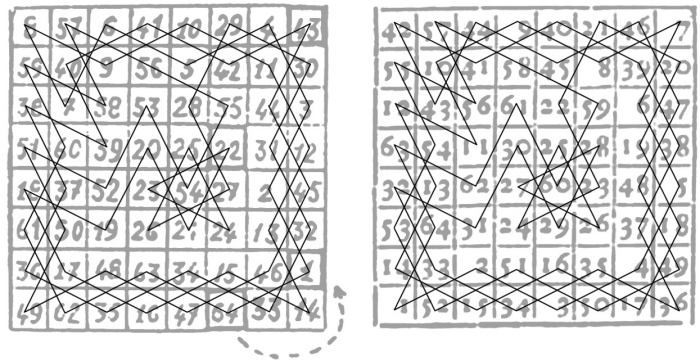

It is the chessboard on the left (compared with Euler's chessboard on the right):

On the left: the Knight's Tour given by Plantard on 1964 (in Jean-Luc Chaumeil, Le testament du Prieuré de Sion, p.122) - On the right: the Knight's Tour given by Euler on 1759. Who inspired who?

The fact they use the same path is far from obvious, but it becomes clear when the two tours are drawn in bold:

Another way of getting new paths is by rotating the chessboard. The author of the parchment did it by rotating the chessboard by 180 degrees.

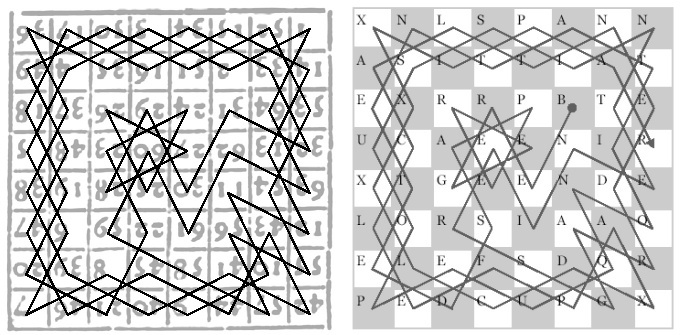

On the basis of Euler's text, the author choose one of the squares (the sixth on the third row) and followed the tour by writing a half of the message:

BERGERE PAS DE TENTATION QUE POUSSIN TENIERS GARDENT LA CLEF PAX DCLXXXI PAR

On the right, Euler's tour rotated by 180 degrees - On the left, the same tour used by the author of the parchment for the first half of the message.

In order to write the second half of the message, the author "recycled" a second time the same tour, by flipping it along the horizontal axis (Douglas Hofstadter uses the term "lake symmetry") and writing the last 64 letters:

LA CROIX ET CE CHEVAL DE DIEU J'ACHEVE CE DAEMON DE GARDIEN A MIDI POMMES BLEUES

On the right, Euler's tour is rotated and lake-flipped - On the left, the same tour is used by the author for the second half of the message.

The resulting text on the first and second chessboard consists of an anagram of the BERGERE message(8):

XNLSPANNASITTIATEXRRPBTEUCAEENIRXTGEENDELORSIAAOELEFSDQRPEDCUPGX

AIEMUIDOCEJDNMEGMCOCEEPDSHRXAIADHATMOAESEBICELERNEEAIEEDLVEVULDC

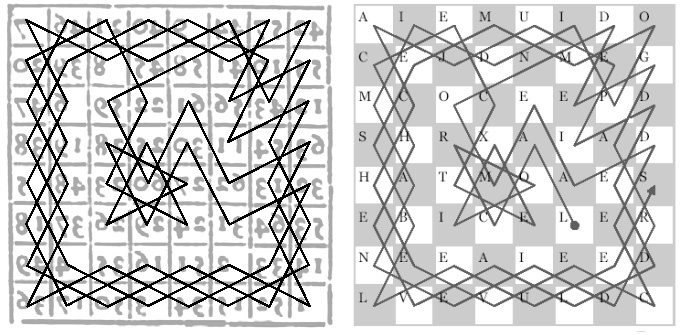

The author was not sufficiently satisfied by this first anagram and decided to emply two keys on the text with the help of a 25 letter Vigenère table (see it here)(9).

The first key was the same 128 letters text taken from the CT GIT and REDDIS stones. The author reversed it by getting:

MUCEARPSPECAPNITACSEIUQERIXXXLOCDMREIVNAJIIVXELEEDECEDSNATPESETNA

XIOSEDEEGATROFEHCNALBEDLUOPUAHDEMADSELRADERGENEDEIRAMELBONTIGTC

By applying this key to the text XNLSPANN... the author got this new text(10)

JRINOHXTJNFSDTQZDTYMGFCZCSCGGBSOSGNZUQODBFIVKUNJZHZCNZXDOJMXBKLIZ

KUXBDZJXXIIUXYBEZABRCKZGLCGEHRZCMSIUURADXDJXGPMJZUHHQZQJGPBLEIZ

The choice of the first key was bizarre enough, because MUCEARPS... was itself an anagram of the text to be encrypted XNLSPANN... (as if we had applied the key COSTUMIER to the words TOM CRUISE).

Just a short note about of how to get from X the letter J by applying the key M; by using this table, locate the column M, go down until you get the X and look at the left: it is the line starting with J. So by applying the key M to the letter X you get J.

This is a "reverse" use of the Vigenère table, which will enable the reader to use a "direct" Vigenère table in order to start from J and M to get X (see here the interaction between the string JRINOHXT... and the key MUCEARPS... which gives XNLSPANN...).

A second (less obvious) key was defined by observing the CT GIT stone, which in the given reproduction shows some errors. Some letters were smaller: e, E, E, P; a M was isolated, the date of death has an anomalous O, the R in ARLES was wrong because the countess came from "Ables" and in the first row the T replaced the more correct I. Properly rearranged, the eight letters formed MORT and EPEE ("death" and "sword").

The author used the 8 letters as a key on the text JRINOHXT..., getting(11):

VCPSJQROVYMYYDLTPEFRBOXTODJLBKNJFQUEPAJYNPPBFEIELRGHIIRYBTTCVTGDL

UCCVMTEJHPNPGSVQJHGMLFTSVJLZQMTOXANPEMUPHKORPKHVJCMCATLVQXGGNDT

At the center of these 128 letters the author inserted the first message AD GENESARETH, which results in a final text 140 letters long:

VCPSJQROVYMYYDLTPEFRBOXTODJLBKNJFQUEPAJYNPPBFEIELRGHIIRYBTTCVTGDADGENE

SARETHLUCCVMTEJHPNPGSVQJHGMLFTSVJLZQMTOXANPEMUPHKORPKHVJCMCATLVQXGGNDT

The Latin Gospel

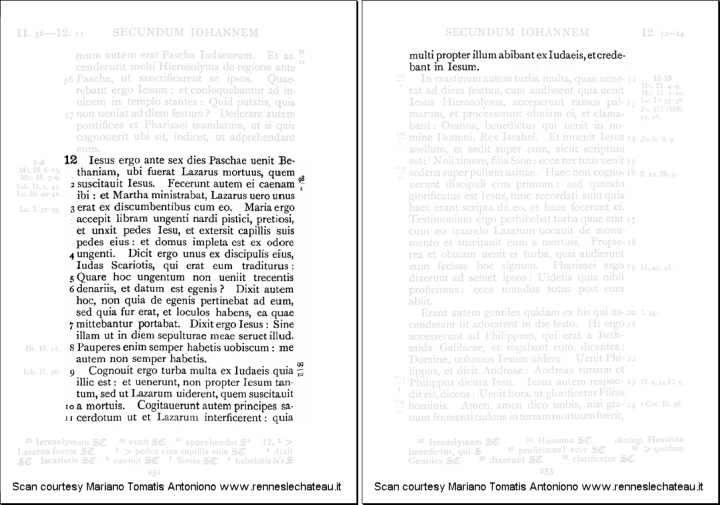

The author looked for a Latin text from the Gospel in which to hide the 140 letters and he chose a chapter from the Gospel of John (12:1-11) with a number of connections with the church in Rennes-le-Château, involving Lazarus, Martha and Mary, the three brothers from Bethania. In particular, the text told the story of the woman anointing Jesus' feet. Some traditions identify Mary of Magdala and Mary of Bethania, the main character of this text, and in Rennes-le-Château there are so many references to Magdala and Bethania. Moreover, the church hosts a stained glass showing Lazarus' resurrection and another one with a woman anointing Jesus' feet.

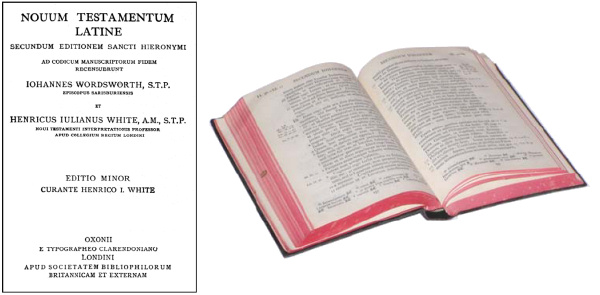

Probably the author obtained the text from a book published in Oxford in 1889: the Novum Testamentum Latine Secundum Editionem Sancti Hieronymi by bishop John Wordsworth and Professor Henry Julian White (download). The hypothesis was suggested for the first time by Bill Putnam and John Edwin Wood(12).

Having personally found a copy of the book, I could compare word by word the Gospel and the text on the Parchment. The two are almost the same, with the exception of the words "odore ungenti", which on the parchment are swapped ("ungenti odore").

John Wordsworth and Henry Julian White (ed.), Novum Testamentum Latine Secundum Editionem Sancti Hieronymi, Oxford (1st ed. 1889, here in the 1950 edition).

Iesus ergo ante sex dies Paschae uenit Bethaniam, ubi fuerat Lazarus mortuus, quem suscitauit Iesus. Fecerunt autem ei caenam ibi : et Martha ministrabat, Lazarus uero unus erat ex discumbentibus cum eo. Maria ergo accepit libram ungenti nardi pistici, pretiosi, et unxit pedes Iesu, et extersit capillis suis pedes eius : et domus impleta est ex odore ungenti. Dicit ergo unus ex discipulis eius, Iudas Scariotis, qui erat eum traditurus : Quare hoc ungentum non ueniit trecentis denariis, et datum est egenis ? Dixit autem hoc, non quia de egenis pertinebat ad eum, sed quia fur erat, et loculos habens, ea quae mittebantur portabat. Dixit ergo Iesus : Sine illam ut in diem sepulturae meae seruet illud. Pauperes enim semper habetis uobiscum : me autem non semper habetis. Cognouit ergo turba multa ex Iudaeis quia illic est : et uenerunt, non propter Iesum tantum, sed ut Lazarum uiderent, quem suscitauit a mortuis. Cogitauerunt autem principes sacerdotum ut et Lazarum interficerent : quia multi propter illum abibant ex Iudaeis, et credebant in Iesum.

The process of inserting the messages inside the Gospel text

The text from Wordsworth/White Gospel was written on 20 rows:

1. IESUS ERGO ANTE SEX DIES PASCHAE VENIT BETHANIAM UBI

2. FUERAT LAZARUS MORTUUS QUEM SUSCITAVIT IESUS FECERUNT

3. LAUTEM EI CAENAM IBI ET MARTHA MINISTRABAT LAZARUS

4. VERO UNUS ERAT EX DISCUMBENTIBUS CUM EO MARIA ERGO ACCEP-

5. IT LIBRAM UNGENTI NARDI PISTICI PREZIOSI ET UNXIT PE-

6. DES IESU ET EXTERSIT CAPILLIS SUIS PEDES EIUS ET DOMUS IM-

7. PLETA EST EX ODORE UNGENTI DICIT ERGO UNUS EX DISCIPUL-

8. IS EIUS IUDAS SCARIOTIS QUI ERAT EUM TRADITURUS QUARE HOC UN-

9. BENTUM NON VENIIT TRECENTIS DENARIIS ET DATUM EST E-

10. GENIS? DIXIT AUTEM HOC NON QUIA DE EGENIS PERTINEBAT

11. AD EUM SED QUIA FUR ERAT ET LOCULOS HABENS EA QUAE MITTEBA-

12. NTUR PORTABAT DIXIT ERGO IESUS SINE ILLAM UT IN DIEM S-

13. EPULTURAE MEAE SERVET ILLUD PAUPERES ENIM SEMPER HA-

14. BETIS VOBISCUM ME AUTEM NON SEMPER HABETIS COGNO-

15. VIT ERGO TURBA MULTA EX IUDAEIS QUIA ILLIC EST ET VENE-

16. RUNT NON PROPTER IESUM TANTUM SED UT LAZARUM VIDER-

17. ENT QUEM SUSCITAVIT A MORTUIS COGITAVERUNT AUTEM P-

18. RINCIPES SACERDOTUM UT ET LAZARUM INTERFICERENT Q-

19. UIA MULTI PROPTER ILLUM ABIBANT EX IUDAEIS ET CRED-

20. EBANT IN IESUM

During the copying process, there have been some irregularities: 27 errors, 2 [additional letters] and 12 omitted letters _

1. IESUS ERGO ANTE SEX DIES PASCHAE VENIT BETHANIAM UAI

2. FUERAT LAZARUS MORTUUS QUEM SUSCITAVIT IESUS FECERUNT

3. LAUTEM EI CAENAM IBI ET MARTHA MINISTRABAT LAZARUS

4. VERO UNUS ERAT EX DISCUMLENTILUS CUM _ _ MARIA ERGO ACCEP-

5. IT LIBRAM UNGENTI NARDI PISTICI PREZIOSI ET UNXIT PE-

6. DES IERU ET EXTERSIT CAPIIRIS SUIS PEDES ERTT ET DOMES IM-

7. PLETA EST EX UNGENTI ODARE DIXAT ERGO UNUM EX DISCIPUL-

8. IS EIUX IUDDX SCARIOTIS QUI ERAT CUM TRADITURUS QUARE HOC UN-

9. BENTUM NON VENIIT TRECENPIS DENARIIS ET DATUM EST E-

10. GENIS? DIXI_ _UTEM HOC NON QUIA DE EGENIS PERTINEBAT

11. AD EUM SED QUIA FUR ER_T ET LOCULOS HABENS EA QUAE MITTEBA-

12. NTUR POR_ABET DIXIT ERGO IESUS SINE ILLAM UT IX DIEM S-

13. EPULTURAE MEAE SERNET ILLUD PAUPERES ENIM SEMPER HA-

14. BETIS NOB[I]ISCUM ME AUTEM NON SEMPER HABETIS COGNO-

15. VIT ER_O TURBA MULTA EX IUDACIS QUIA ILLIC EST ET VENE-

16. RUNT NON PRO_TER IESUM TANTUM SED UT L_ZARUM VIDER-

17. ENT QUEM SUSC_TAVIT A MORTUIS COGITAVERUNT AUTEM P-

18. RINCIPES SACERDOTUM UT ET LAZARUM INTERFICERENT Q-

19. UIA MULTI PROPTER ILHUM ABIB_NT CX _U[T]DAEIS ET CRCD-

20. EBANT IN IESUM

The text was divided into groups of 6 letters each, with seven irregularities (stressed with an asterisk *)

1. IESUSE RGOANT ESEXDI ESPASC HAEVEN ITBETH ANIAMU AI...

2. ...FUERA* TLAZAR USMORT UUSQUE MSUSCI TAVITI ESUSFE CERUNT

3. AUTEME ICAENA MIBIET MARTHA MINIST RABATL AZARUS

4. VEROUN USERAT EXDISC UMLENT ILUSCU MMARIA ERGOAC CEP...

5. ...ITL IBRAMU NGENTI NARDIP ISTICI PRETIO SIETUN XITPE...

6. ...D ESIERU ETEXTE RSITCA PIIRIS SUISPE DESERT TETDOM ESIM...

7. ...PL ETAEST EXUNGE NTIODA REDIXA TERGOU NUMEXD ISCIPU L...

8. ...ISEIU XIUDDX SCARIO TISQUI ERATCU MTRADI TURUSQ UAREHO CUN...

9. ...BEN TUMNON VENIITT* RECENP ISDENA RIISETD* ATUMES TE...

10. ...GENI S?DIXI UTEMHO CNONQU IADEEG ENISPE RTINEB AT...

11. ...ADEU MSEDQU IAFURE RTETLO CULOSH ABENSE AQUAEM ITTEBA...

12. ...N* TURPO RABET DIXITE RGOIES USSINE ILLAMU TIXDIE MS...

13. ...EPUL TURAEM EAESER NETILL UDPAUP ERESEN IMSEMP ERHA...

14. ...BE TISNOB IISCUM MEAUTE MNONSE MPERHA BETISC OGNO...

15. ...VI TEROT* URBAMU LTAEXI UDACIS QUIAIL LICEST ETVENE

16. RUNTNO NPROTE RIESUM TANTUM SEDUTL ZARUM* VIDER...

17. ...E NTQUEM SUSCTA VITAMO RTUISC OGITAV ERUNTA UTEMP...

18. ...R INCIPE SSACER DOTUMU TETLAZ ARUMIN TERFIC ERENTQ

19. UIAMUL TIPROP TERILH UMABIB NTCXU* TDAEIS ETCRCD

20. EBANTI NIESUM

Between the six-letters-groups, 140 letters from the message were added (but with another three errors). The letters should have been:

VCPSJQROVYMYYDLTPEFRBOXTODJLBKNJFQUEPAJYNPPBFEIELRGHIIRYBTTCVTGDADGENE

SARETHLUCCVMTEJHPNPGSVQJHGMLFTSVJLZQMTOXANPEMUPHKORPKHVJCMCATLVQXGGNDT

8 letters were put in superscript, so coding a new message (REX MUNDI).

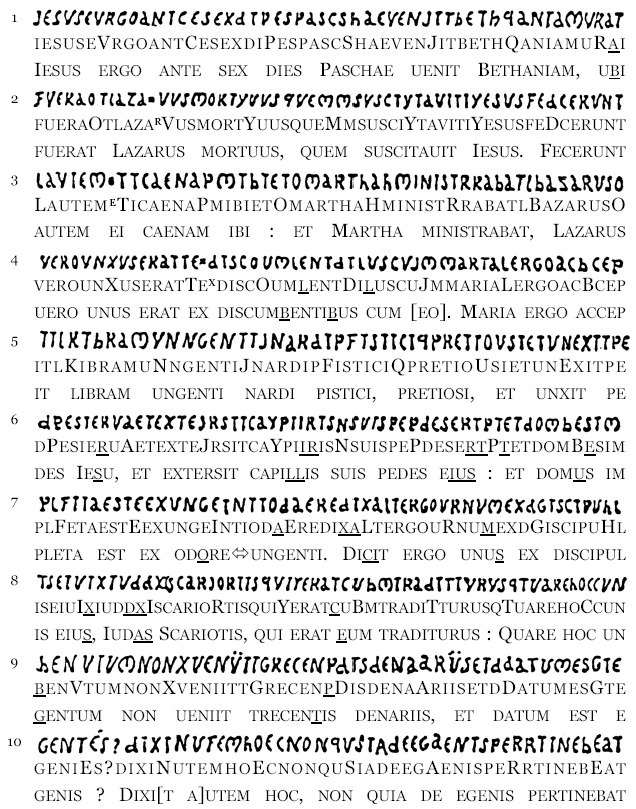

1. IESUSEVRGOANTCESEXDIPESPASCSHAEVENJITBETHQANIAMURAI

2. FUERAOTLAZARVUSMORTYUUSQUEMMSUSCIYTAVITIYESUSFEDCERUNT

3. LAUTEMETICAENAPMIBIETOMARTHAHMINISTRRABATLBAZARUSO

4. VEROUNXUSERATTEXDISCOUMLENTDILUSCUJMMARIALERGOACBCEP

5. ITLKIBRAMUNNGENTIJNARDIPFISTICIQPRETIOUSIETUNEXITPE

6. DPESIERUAETEXTEJRSITCAYPIIRISNSUISPEPDESERTPTETDOMBESIM

7. PLFETAESTEEXUNGEINTIODAEREDIXALTERGOURNUMEXDGISCIPUHL

8. ISEIUIXIUDDXISCARIORTISQUIYERATCUBMTRADITTURUSQTUAREHOCCUN

9. BENVTUMNONXVENIITTGRECENPDISDENAARIISETDDATUMESGTE

10. GENIES?DIXINUTEMHOECNONQUSIADEEGAENISPERRTINEBEAT

11. ADEUTMSEDQUHIAFURELRTETLOUCULOSHCABENSECAQUAEMVITTEBA

12. NMTURPOTRABETEDIXITEJRGOIESHUSSINEPILLAMUNTIXDIEPMS

13. EPULGTURAEMSEAESERVNETILLQUDPAUPJERESENHIMSEMPGERHA

14. BEMTISNOBLIISCUMFMEAUTETMNONSESMPERHAVBETISCJOGNO

15. VILTEROTZURBAMUQLTAEXIMUDACISTQUIAILOLICESTXETVENE

16. ARUNTNONNPROTEPRIESUMETANTUMMSEDUTLUZARUMPVIDER

17. EHNTQUEMKSUSCTAOVITAMORRTUISCPOGITAVKERUNTAHUTEMP

18. RVINCIPEJSSACERCDOTUMUMTETLAZCARUMINATERFICTERENTQ

19. LUIAMULVTIPROPQTERILHXUMABIBGNTCXUGTDAEISNETCRCD

20. DEBANTITNIESUM

The final text was written without spaces and completed by:

- two small symbols at the top and at the bottom which seem to be rudders;

- a sort of signature "NOIS" which can be read as SION when inverted;

- the text taken from the inscription at the foot of the altar in the church of Rennes-le-Château before someone stole it.

The inscription at the foot of the altar, now stolen

Here is the final parchment:

Gérard de Sède, L'Or de Rennes, Paris: Julliard, 1967, p.109

In order to complete the analysis of the parchment I wrote a line by line transcription which compares the pseudo-uncial text (line 1), the transcription (line 2) and the text of the Gospel in the edition "Wordsworth and White".

In line 2 the letters taken from the 140 letters message are written with a larger font.

For a correct reading it is necessary to keep in mind these notes:

1) On the parchments the letters I and T and the letters V and U are almost the same; during the transcription, priority was given to the letters on the Gospel "Wordsworth and White", with the exception of the U which is always copied as V when the meaning is clear;

2) Sometimes also the letters C and E are very similar: in these cases the error is emphasised;

3) When two letters (from the parchment and from the Gospel) are different, in both lines 2 and 3 the letters are underlined, in order to locate them with ease;

4) Some letters on the parchment are written with a smaller font: in the transcription they have been put in superscript. When read in sequence, they give REX MUNDI (rows 2, 3, 4, 16, 17, 19, 20);

5) On two occasions the parchment misses some letters from the Gospel: in these cases the omitted letters are between [square brackets] on line 2 (rows 14 and 19);

6) Sometimes the parchment misses some letters from the Gospel: in these cases the omitted letters are between [square brackets] on line 3 (i.e. at row 4 where the letters EO are omitted from the parchment).

A final note: the author of the parchment did many errors in creating it, but the worse was certainly the one made during the copy of the 140 letters of the hidden message; three letters were mis-copied (two letters EF became OH and a letter T became X).

With those errors, the 140 letters produce a message like this:

BERGETE PAS DE TENTATION QUE POUSSIN TENIERS GARDENT LA CLEF SAX DCLXHXI PAR LA CROIX ET CE CHEVAL DE DIEU J'ACHEVE CE DAEMON DE GARDIEN A MIDI POMMES BLEUES

The one given above is the message really hidden inside the Great Parchment. It is interesting to note that since 1965 the message was always mentioned with the three corrections (BERGERE, PAX and DCLXXXI), although the parchment is wrong (being the words BERGETE, SAX and DCLXHXI). The correct reading is arbitrary and based only on an interpretation driven by the sense of the final message, but not justified by any other element on the parchment.(13)

_________________

(1) Ferdinando Ferraioli, "Indagine paleografica sulle due pergamene" in Indagini su Rennes-le-Château 14 (2007) pages 694-698.

(2) See: Mariano Tomatis Antoniono, "Le fonti di Pierre Gravées du Languedoc - Storia e controstoria di un intricato falso" in Indagini su Rennes-le-Château 20 (2008), pages 982-994.

(3) See: Marco Cipriani e Mariano Tomatis Antoniono, "La stele tombale di Marie de Nègre d'Ables - Approfondimento storico documentale" in Indagini su Rennes-le-Château 6 (2006) pages 293-303.

(4) Stefano Bartezzaghi, Lezioni di enigmistica, Torino: Einaudi, 2001, p.119.

(5) Euler, "Solution d'une question curieuse qui ne paroit soumise à aucune analyse" in Memoires de l'Academie Royale des Sciences et Belles Lettres (1759) 15, Berlin: 1766, page 312.

(6) Euler suggested the rule of rotating the chessboard ("3. [...] Il est évident, que cette route satisfait également, quand on veut commencer par quelqu'un de autres angles".), the rule of inverting the path ("4. En retournant par la meme route on pourra aussi commencer par la case 64, & de là en passant successivement par les cases 63, 62, 61, &c. on parviendra enfin, après avoir parcouru toutes les cases, à celle du coin 1".) and the rule of changing starting position ("6. [...] On pourra commencer par quelque case que ce soit, & de là continuer la course suivant l'ordre des nombres jusqu'à la case marquée par 64, d'où, en sauntant à la celle qui est marquée par 1, il acheveroit la course jusqu'à retourner à celle d'où il étoit parti".). See Euler, "Solution d'une question curieuse qui ne paroit soumise à aucune analyse" in Memoires de l'Academie Royale des Sciences et Belles Lettres (1759) 15, Berlin: 1766, page 311-312

(7) Jean-Luc Chaumeil, Le testament du Prieuré de Sion, pages 115-122.

(8) The same sequence can be found on the manuscript attributed to Philippe de Chérisey "Pierre et Papier". The same sequence - in an inverted form - can be found also on "Circuit", by the same author.

(9) The process has been fully explained by Mariano Tomatis Antoniono in The Rennes-le-Château Observer, volume 50 (2007)

(10) The same sequence (with three differences) can be found on the manuscript attributed to Philippe de Chérisey "Pierre et Papier" and on the book by the same author "Circuit". The differences are underlined here:

JRINOHXTJNFSDTQZDEAMGFCZCSCGGBSO

SGNZUQODBFIVKUNJZHZCNZXDOJMXBNLI

ZKUXBDZJXXIIUXYBEZABRCKZGLCGEHRZ

CMSIUURADXDJXGPMJZUHHQZQJGPBLEIZ

With these corrections (otherwise unjustified), the final text is correct, but De Chérisey offers no justification for the use of these correct letters.

(11) The same sequence (with three differences) can be found on the manuscript attributed to Philippe de Chérisey "Pierre et Papier" and on the book by the same author "Circuit". The differences are underlined here:

VCPSJQROVYMYYDLTPOHRBOXTODJLBKNJ

FQUEPAJYNPPBFEIELRGHIIRYBTTCVXGD

LUCCVMTEJHPNPGSVQJHGMLFTSVJLZQMT

OXANPEMUPHKORPKHVJCMCATLVQXGGNDT

With these corrections (otherwise unjustified), the final text is correct, but De Chérisey offers no justification for the use of these correct letters.

(12) Bill Putnam and John Edwin Wood, The Treasure of Rennes-le-Château - A Mystery Solved, Sutton Publishing, 2005

(13) Translation by Mariano Tomatis with the precious help of Marcus Williamson.